Tim Senior

Shirley Evans

COVID-19 has changed for us all what it means to be ‘creative and connected’. Whilst physical distancing measures have helped shield many with a dementia from the virus, its negative impact on people’s physical and mental wellbeing is now also clear. As traditional care models are overturned, the challenge of keeping people safe, creative and connected calls for new ideas. ‘Our Memory Jars’ – developed in partnership between supersum, artists Alison Neighbour and Kate Lovell, and the UK Meeting Centres programme – is one such experiment.

A Disproportionate Impact

For people living with a dementia, the risk of contracting COVID-19 has been disproportionately high: 94% of COVID-19-related deaths in March to June 2020 were amongst those over 60, with 28% of those (in England and Wales) recording a dementia diagnosis (1, p. 15-16). (For reference, 7% of people over 65 have a dementia; 2). As a recent report from the Alzheimer’s Society starkly reminds us, whilst physical distancing helps shield many from the virus, it does not protect people from their dementia (1). One impact of physical distancing has been to drive a reported rise in loneliness and isolation (1, p. 27), increased dementia symptoms, and a decline in both cognitive abilities and physical wellbeing (1, p. 28). Whilst self-isolation and social-distancing is a problem for people with a dementia and their families during COVID-19, reports from the last eight months only bring to attention a long-standing issue.

Communication technologies (such as video conferencing and online chat platforms) have proven useful in reaching out to people, helping deliver the kind of support and face-to-face engagement critical in everyday care. Although great strides have been made in keeping people connected, technology-use is not, however, a catch-all solution: many either don’t have access to these services, don’t wish to use them, or would prefer to engage person-to-person whenever possible. At the beginning of the pandemic, a number of UK Meeting Centres quickly developed virtual Meeting Centre formats, supporting members and carers to meet online in small groups. In this process, Meeting Centres helped participants gain access to online platforms, learn digital skills, and adjust to online forms of engagement. Reaching around 40% of the membership, a question emerged early on whether members without access to technology might be helped to interact with each other, whilst still respecting physical distancing guidance.

From Hub to Network

Meeting Centres play an important role in helping people with a dementia live well in their communities and cope better with the transitions that dementia brings (3). Under normal circumstances, Meeting Centres offer a centralised resource of expertise, support and social engagement – a form of ‘hub and spoke’ model that brings individual members together into one place to receive care. At the centre, staff facilitate group activities driven by the wishes and interests of the members; each day at a Meeting Centre is different. Under physical distancing guidance, Meeting Centres have faced an inversion of this model, forced to develop resources centrally that are then sent out to members in their own homes or accessed online (e.g. telephone buddies, newsletters, online and posted materials). The impact of this inversion has been considerable: what was social, dynamic, and resource-efficient at the hub becomes more asocial, resource-intensive, and repetitious at the spokes. At Leominster, Kirriemuir, Powys, and elsewhere, Meeting Centre staff have worked tirelessly to tackle the challenges that this inversion of their support model brings.

If technology offers only a partial solution to helping people interact with each whilst remaining physically distanced, are there other forms of interaction that don’t require technology and can draw strength from the distributed (rather than centralised) nature of Meeting Centre members at this time? Can we imagine a model where each participant in a Meeting Centre’s life (members, carers, staff or volunteers) becomes a source of creativity for the whole group; where participants can reach out to each other, so shaping the group’s collective experience; where creative activities can take on a life of their own within the group (a culture of creativity), rather than being managed centrally. In other words, can we imagine a distributed network where each participant plays an equal role, contributing to a self-sustaining group activity that keeps people creative and connected.

Our Memory Jars

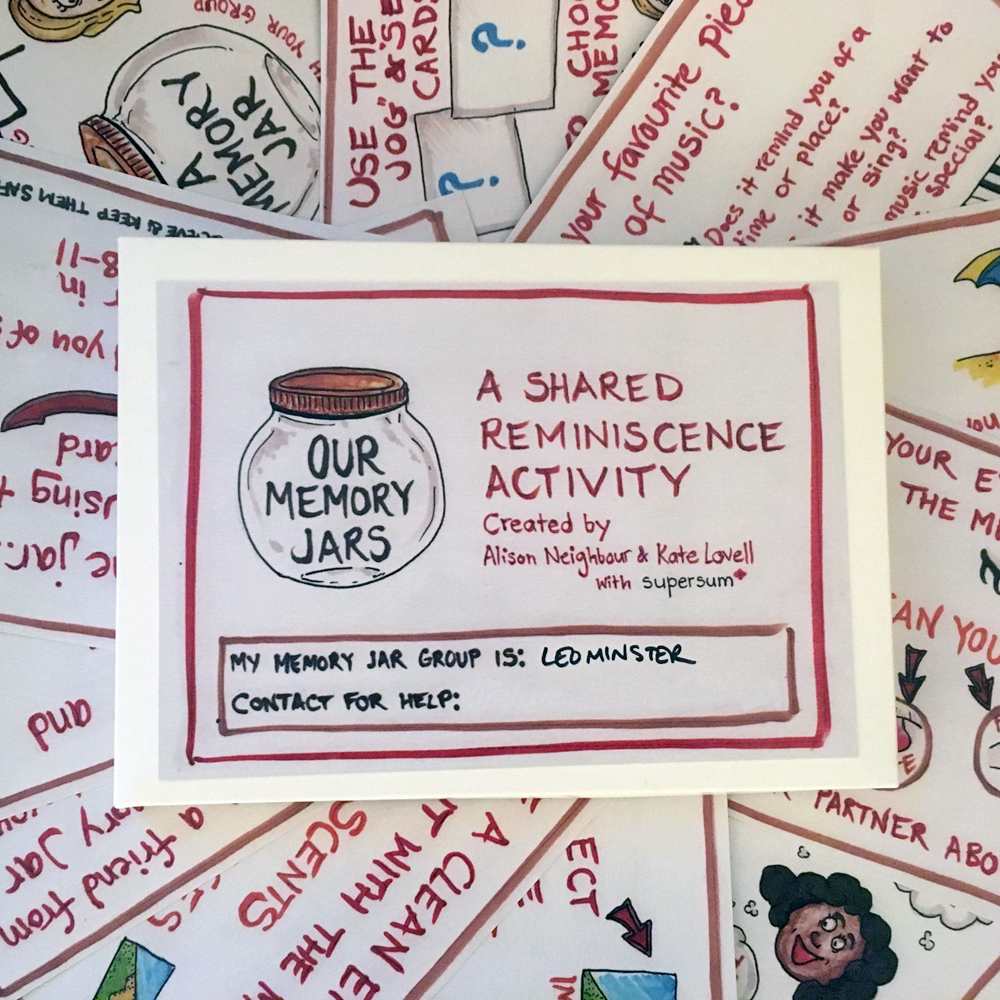

Fig1: A pack of 12 cards taking you through a creative reminiscence activity

Our Memory Jars

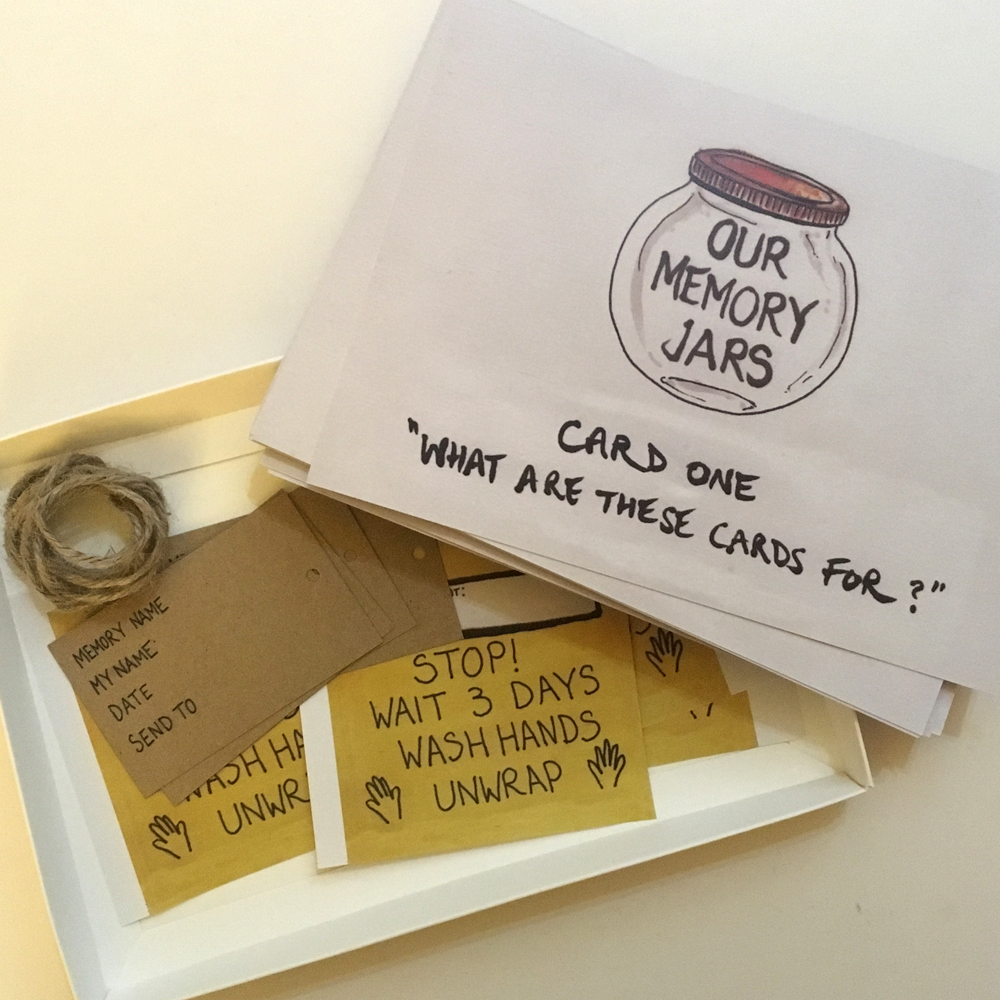

Our starting point in response to this challenge is a favourite of many creative support routines: Memory Jars. Here, a reminiscence activity in a group supports the recreation of fond memories (from everyday items) in jam jars. It’s an activity that uses making to support individual and social storytelling. Working with artists Alison Neighbour and Kate Lovell (whose project The Memory Store inspired this work), we have further developed the Memory Jars model to work with socially distanced groups of up to 20 people. Each person in the group receives a pack of prompt cards (Figure 1) that takes them (and a carer or family member who may be supporting them) through a cycle of reminiscence and making activity. What’s changed is that once a memory jar is completed, it is labeled, wrapped and sent to someone else in the Memory Jar group, a little gift for them to unwrap and explore in their own time. This jar becomes the stimulus for another (but different) reminiscence process and the creation of a second jar, to be sent to a third person, and so on – the start of a chain reaction that transforms every time a new Memory Jar is made. The pack includes all the instructions and materials needed to make jars and send them safely. This includes pre-printed labels (to attach to wrapped jars) telling the receiver to isolate the jar for three days before opening, and to wash their hands after handling (Figure 2). The idea is simple enough, but has a lot to offer in terms of the distributed network model described. It’s a way to:

- help members be creative in their own right and inspire creativity in others;

- build anticipation, thoughtfulness, and spontaneity into creative activities;

- support members to learn more about each other and strengthen relationships;

- sustain creativity over a longer period of time, whilst also generating its own renewal;

- bring more members (without technology access) into a shared experience;

- engage the membership with proportionally less demand on the Meeting Centre.

Safety first

Fig2: The activity is designed to be COVID-19 safe

A Clumsy Solution?

Supersum’s work centres on Wicked Problems, a type of problem that is not easily defined and solved to the satisfaction of different parties seeking its resolution. Keeping people creative and connected during COVID-19 is a Wicked Problem in that those implicated (people affected by dementia, their families, carers, and organisations such as Meeting Centres) bring different perspectives on the nature of the problem and how best to resolve it. Wicked Problems demand Clumsy Solutions. With our focus on social life, Clumsy Solutions are those that creatively draw on different types of social ‘building block’ to generate social action that benefits the majority of those involved. The different forms of social building block at play are Hierarchy, Individualism, Egalitarianism, and Fatalism. Solutions to wicked problems that are built on only one social building block are unlikely to succeed in the long term. Consider, for example, an approach to the current challenge based on a turn to Individualism alone, i.e. “everyone for themselves”: whilst some will have the social and financial means to be creative and connected under COVID-19, many will become even more marginalised – a call for external care support (a hierarchical element) that takes the welfare of the whole group (and group solidarity) into account.

Meeting Centres by their very nature are ‘clumsy’, and their response to COVID-19 (in many cases agile, reflexive, and drawing on different forms of social life) points to the strength of their approach. ‘Our Memory Jars’ tries to capture this same ‘clumsy’ spirit: An activity designed by expert art practitioners in the field (Hierarchy) makes room for individual expression (Individualism) and a richer, collective meaning making amongst Meeting Centre members (Egalitarianism), whist also able to accommodate incomplete uptake (for reasons that may include Fatalism). This clumsy structure cuts all the way through the project. In relation to COVID-19 safety, for example, the activity is designed to be as safe as possible (drawing on a detailed risk assessment), with Meeting Centres there to encourage (or pause) the activity in their professional safe-guarding role. From the perspective of individual participants, this activity is completely voluntary, with no requirement for anyone to complete or send Memory Jars. Yet, if enough people choose to participate, the activity goes ahead – an opportunity to see how it can work safely to the benefit of everyone together.

Looking Ahead

‘Our Memory Jars’ is an experiment: It may not catch on, or it could catch on in ways we don’t expect. Four very different groups are beginning to trial the activity, and future insight posts will look in detail at those experiences. There are certainly questions we hope to explore, such as how the in-group familiarity of a membership impacts the way Memory Jars are made and exchanged; whether there are benefits to including an online component – a route to introduce new ideas, themes and participants into the activity; or whether the activity might find a purpose in ‘normal’ times when Meeting Centres (and other community-embedded initiatives) are once again fully operational. Whether Our Memory Jars can become part of a ‘culture of making’ amongst participants (one that complements the work of a more traditional activity coordinator) will have to be seen.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Western Power Distribution for funding this work

References

1) Alzheimer’s Society (2020). Worst hit: Dementia during coronavirus. London: Alzheimer's Society. Available online at https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-09/Worst-hit-Dementia-during-coronavirus-report.pdf